How Childhood Shapes the Nervous System (Trauma Series Part 3)

By Nhi Vo, LMSW | Clove Counseling, Lisle IL

In earlier posts, we talked about how trauma is less about one “big” event and more about what happens inside us when we feel overwhelmed and alone. In this part, we will look at how childhood experiences shape the nervous system itself.

You do not need to be a neuroscience expert for this to matter. Understanding even a little bit about your nervous system can make your feelings and reactions feel much less mysterious.

Your Nervous System Is Your Built-In Safety Radar

The nervous system is your body’s communication and alarm system. It includes your brain, spinal cord, and all the nerves running through your body. It constantly sends and receives messages about what’s happening inside you and around you, helping you react to danger, calm down when you are safe, feel emotions, move your muscles, and notice sensations like pain, warmth, or hunger.

You can think of it like your internal “control center,” constantly scanning your world and asking:

“Am I safe, or am I in danger?”

It does this mostly outside of conscious awareness.

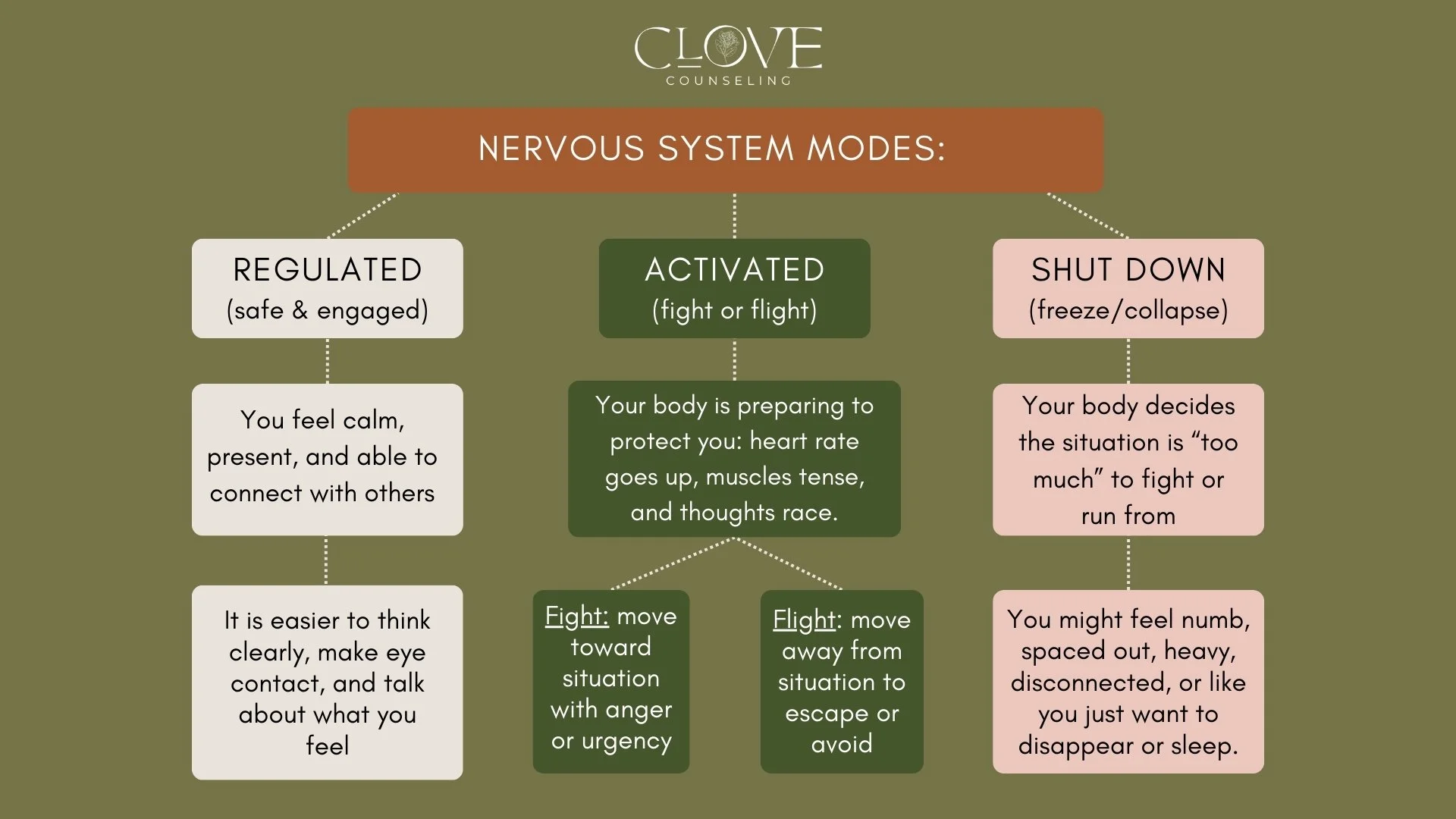

Using ideas from Polyvagal Theory and developmental neuroscience, we can think of your nervous system as having a few main modes ¹ ²:

Regulated or engaged: You feel relatively safe, present, and connected.

Activated (fight or flight): Your body prepares to protect you by getting activated. You might feel anxiety, anger, racing thoughts, or restlessness.

Shutdown (freeze): Your body pulls back to conserve energy. You may feel numb, detached, exhausted, or “checked out.”

None of these states are good or bad. They are all survival responses.

The patterns your nervous system relies on most often usually come from childhood.

The Window of Tolerance & How Early Experiences Can Shrink it Overtime

How quickly you move from a regulated state to activation or shutdown depends on your window of tolerance. You can think of your window of tolerance as your nervous system’s “comfort zone,” the range where you can feel emotions and stress while still staying present, thinking clearly, and staying connected to yourself and others. When you are inside your window, hard feelings can show up, but they feel manageable. When stress gets too big, your nervous system can get pushed outside that window, from a state of regulation to either activation or shutdown.

A helpful thing to know is that your window is not fixed. It can widen or narrow over time based on what your nervous system has had to adapt to. Repeated stress, trauma, or ongoing emotional invalidation can make the window narrower, which means it takes less to push you into activation or shutdown.

The biosocial model in Dialectical Behavior Therapy (DBT) explains the window of tolerance as a loop: some people are born with a more sensitive emotional system, and if they grow up in an environment that regularly dismisses, punishes, or ignores emotions, they may not get enough support or skills to return to baseline. Over time, because they’ve stayed in a dysregulated state for so long, their window of tolerance may restrict and the nervous system then learns to default to protection more quickly³ ⁴.

Here are two examples of how this can happen:

Example 1: Defaulting to activation (fight or flight)

A child grows up in a home where tension is unpredictable. They learn to constantly scan for mood shifts, conflict, or danger. That hyper-alert state helps them cope in the moment, but over time their nervous system starts to treat “uncertainty” as unsafe. As an adult, small stressors (a delayed text, a critical tone, an unexpected change) can create a big surge of anxiety or anger because the body is already primed to protect.

Example 2: Defaulting to shutdown (freeze)

A child expresses sadness, fear, or need and those feelings are minimized or never addressed. Maybe a big event happens and nobody talks about it. Maybe the child reaches out in a serious way and it is met with silence. Over time, the nervous system learns that having needs does not lead to support, so it adapts by going numb, quiet, or “fine.” As an adult, they may freeze in conflict, go blank in emotionally intense moments, or feel disconnected from what they want or feel.

Basically, Childhood Is When Your Nervous System Learns the Rules

Children learn about safety from experiences, not lectures:

Does someone come when I cry?

What happens when I express anger or sadness?

Are mistakes treated with curiosity or shame?

Do I get comfort, or do I get ignored, mocked, or punished?

Is the environment predictable or chaotic?

Over time, your nervous system builds an internal map:

“People are safe” or “people are not safe.”

“My feelings are manageable” or “my feelings are dangerous.”

“I can rely on others” or “I must rely only on myself.”

When kids repeatedly experience misattunement, fear, or emotional isolation, their nervous system often learns to stay in fight or flight or in freeze more often ⁵ ⁶.

The Role of Co-Regulation

We are not born knowing how to calm ourselves. We learn this through co-regulation, another person’s calm and steady presence that helps our system settle⁷.

For example:

A toddler cries, a caregiver comes close, speaks gently, and offers comfort. Over time, the child’s body learns, “Feelings rise and fall. I am not alone.”

A teen is anxious, and a parent listens, validates, and helps problem-solve instead of shutting them down or minimizing their feelings. The teen’s body learns, “Big feelings can be shared and survived.”

If caregivers are overwhelmed, emotionally unavailable, frightened, or critical, children may learn instead:

“My feelings are a problem.”

“I deal with this alone.”

“Needing others is dangerous or embarrassing.”

This does not mean caregivers were bad people. Often, they were doing the best they could while carrying their own unresolved stress or trauma.

Still, the nervous system remembers the pattern.

Adolescence: Big Feelings and a Changing Brain

Adolescence is an intense time. The brain regions responsible for emotion develop faster than the regions responsible for long-term planning and impulse control ⁸. That is one reason why everything can feel so big, urgent, or world-ending in the teen years ² ⁹.

If teens do not have emotionally safe adults to turn to, they may turn to:

numbing through social media, substances, or zoning out

perfectionism and overachieving

people-pleasing

self-harm or other risky behaviors

These are attempts to manage an overloaded nervous system, even when they are risky or harmful.

How All This Shows Up in Adulthood

If your nervous system learned early that emotions were not safe or that no one would reliably help, you might notice as an adult:

getting flooded or shutting down in conflict

feeling like you “overreact” and then criticizing yourself afterward

avoiding vulnerability because it feels dangerous

having a hard time trusting that support will be there

swinging between feeling numb and feeling overwhelmed

These are not character defects. They are nervous system patterns that were wired in early. They can be updated.

The Hope: Neuroplasticity and New Experiences

The good news is that the brain and nervous system can change throughout life ² ⁶.

Healing trauma is not about erasing the past. It is about:

giving your nervous system new experiences of safety

practicing co-regulation with safe others

expanding your window of tolerance, the range where you can feel feelings without becoming overwhelmed

learning to notice and gently shift your states

Therapy can be one place where this happens slowly, safely, and at your own pace.

Coming Next: Part 4—How Trauma Shows Up in Adulthood

In the next post, we will look at common ways trauma shows up in adult life, including relationships, self-esteem, work, and the body.

Want to get notified when Part 4 is published? Subscribe to our blog below.

(Or check back soon — new posts are on the way.)

Curious About Trauma Therapy at Clove Counseling?

If this resonates with you, I’d love to help.

Learn more or schedule a session at:

References

Porges, S. W. (2017). The Pocket Guide to the Polyvagal Theory: The Transformative Power of Feeling Safe. W. W. Norton.

Siegel, D. J. (2020). The Developing Mind: How Relationships and the Brain Interact to Shape Who We Are (3rd ed.). Guilford Press.

Crowell, S. E., Beauchaine, T. P., & Linehan, M. M. (2009). A biosocial developmental model of borderline personality: Elaborating and extending Linehan's theory. Psychological bulletin, 135(3), 495–510.

Bemmouna, D., & Weiner, L. (2023). Linehan's biosocial model applied to emotion dysregulation in autism: a narrative review of the literature and an illustrative case conceptualization. Frontiers in psychiatry, 14, 1238116.

Schore, A. N. (2019). Right Brain Psychotherapy. W. W. Norton.

Perry, B. D., & Winfrey, O. (2021). What Happened to You? Conversations on Trauma, Resilience, and Healing. Flatiron Books.

Siegel, D. J., & Bryson, T. P. (2020). The Power of Showing Up: How Parental Presence Shapes Who Our Kids Become and How Their Brains Get Wired. Ballantine Books.

Casey, B. J., Jones, R. M., & Hare, T. A. (2008). The adolescent brain. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences, 1124(1), 111–126.

Steinberg, L. (2014). Age of Opportunity: Lessons from the New Science of Adolescence. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt.